How To Kill The Market For Ticket Touting.

- Jimmy Mulvihill

- Jan 22, 2015

- 19 min read

Updated: Mar 9, 2023

by Jimmy Mulvihill

January 22nd 2015

To buy tickets to any major music concert these days you have one of two options: wake up at 8:45am and be at your computer by 9am to keep tapping that F5 button in the hope that you strike lucky, or you can resort to buying them through a tout, or as they are known in North America, a scalper. This can be in the form of a guy from South London wearing a Man Utd beanie cap standing outside the venue (“…..tickets, buy or sell, anyone got any tickets, buy or sell……”) or in the guise of a web company with a high Google ranking, a sleek website, and a wish to part you with as much money as possible. Sadly the odds are not in your favour – for every ticket available for the hottest show in town there may be 10 people wanting it, and so the competition of “who gets them first” turns into a competition of “who is willing to spend the most”. Inevitably by adding another middle man the cost of the ticket will become vastly inflated, and here in lies the conundrum of why this is a topic that genuinely evokes strong emotions on both sides.

There are people who claim that ticket touts are simply offering a service that uses the same market forces as many other businesses do in a legal way: providing a product that people want to the person that wants it. Their argument is that the buyer who buys from the middle man is able to do so without the need of having to plan too much in advance, and that if we were to clamp down on this trade then we would be stepping into a dangerous territory of deciding what people can and can’t do with their own money. If someone was doing the same thing with any other good like vases, paintings or cars then there would be no such objections by the media, and particularly the music press. In any case, who is to say how much is too much for tickets? In fact, they claim, to start dictating what some people can and cannot spend their money on would lead us to a slippery slope of ‘restrictions of trade’. Take it a step further and it would be entering a restriction on personal choice and freedom. Especially since concert tickets are hardly a necessity, their price should be left to the market. With many people finding it hard to find employment, ticket touting provides some with a way to support their family which does not require them to break the law. So concludes the defence's case.

Then there are the people that see touting as the antitheses of everything that is wrong with the music industry; people with no direct involvement in the creation of the music who are profiteering from the talent that bands have, motivated by pure greed, drawing money away from the music industry that does not get re-invested back into it, and exploiting people’s emotional connection with a band for maximum financial gain. They argue that the touts make a bigger profit than the band ever will on a per-ticket basis, often with no tax to be paid from the profit, and that these touts are the scourge of the industry. They may personally benefit from the practice, but at the expense of everyone else, surely?

Maybe. Or maybe not, as I have actually heard the argument that ticket touting is good for the music industry from people within the industry, with the argument being that they are particularly good for the bands whose tickets get touted. The argument is that if a band played a venue that held 2,000 people they may have a good chance of selling 1,500 to 2,000 tickets for it, but some touts may feel (incorrectly perhaps) that the gig has a much better chance than some others of selling out, and so they decide to snap up a bulk amount of tickets en masse. By doing so suddenly the gig is sold out in triple quick time, and many people are left scratching their head thinking, “Wow, that band sold out that venue that quickly? Maybe they must have a bigger fan base than we thought…….” As a result, the prestige of the band is significantly lifted from many people seeing the “sold out” signs and jumping onto the popularity bandwagon, and so the demand for their next shows soar, more dates are added, and the band sells more albums. The (fake) perception of the bands success breeds more (genuine) success, and thus explains a theory that some have that ticket touts are an integral part of the music industry. This explains why so many promoters allow the big ticket agencies to buy up so many tickets of their concerts – nothing promotes a tour better than getting widespread newspaper coverage about how it is the “hottest ticket in town!” and no-one has the power to make bulk purchases than these ticket agencies.

Arctic Monkeys, Belle and Sebastian and Enter Shikari all had a significant bump in their popularity by selling out a short run of albums/a major concert, and all of them had touts both capitalising and contributing to this success, which is not to imply that the success of the band is down to the touts, it is just to say that touts make the popularity of a band more traceable. The touts pay the same rate as the general public for tickets, and the same amount of tickets have been sold whether it is to touts or music fans. The difference is that while touts will not have changed the amount or price of the tickets eventually sold, they would have changed the purchase rate that they were sold at, which is vital as much of the success of a band will ultimately come down to how much confidence people have in them. When touts buy so many of the tickets at once it will remove much of this doubt about whether the gig will sell out, and the touts could be capitalising on the popularity of the band that they have actually played a hand in creating. When a heavy metal band sells out their show at a venue within 1 hour it makes the promoter more likely to think about booking more heavy metal shows.

In a strange way it could be argued that ticket touts are bringing some much needed stability to a notoriously unpredictable industry. In 2013, Justin Bieber played his world tour, “The Believe Tour”, and 99% of it sold out, shifting nearly 900,000 tickets in total. Yet, the concert that was scheduled in Lisbon, Portugal had to be cancelled due to poor sales, mainly due to Portugal being hit hardest by the economic crises out of all of the dates on the tour. People who are in favour of ticket touts will claim that if ticket touts had been able to buy up the tickets for this concert then it would not have been cancelled since the lack of demand for it would only have been discovered on the night, and so the other people who bought tickets could have attended it only as a direct result of the touts affecting the usual levels of supply and demand. In a weird way, in this case the touts would have actually been helping these “Beliebers” out.

The touts are also doing all of this at their own financial risk. After all, in many cases if they cannot shift these tickets they do not have the option of returning them to the box office. Some people would cite this financial commitment and risk they take as reason enough for ticket touts to be able to able to ply their trade in such a way, arguing that in a world where tickets are sold up to 9 months before the concert, any profit that the touts make is more than justified considering they will pay up front for the tickets, but will have to wait so long for a return, with the costs that go along with that. If pay-day loans are able to give £40 to someone to buy nappies and expect to get £500 back in a year’s time, why should tickets touts not expect the same return for a luxury item?

Whilst ticket touting is not illegal and many large companies have made tens of millions of pounds of profits from the back of it, for the majority of people who sell gig tickets at highly inflated prices there is either a cruel opportunism of emotional manipulation, or a certain disingenuous to the activity. When the Stone Roses announced their reunion shows at Heaton Park in Manchester in 2012 the tickets were priced at £55, yet within 10 minutes of them going on sale they were being sold on eBay for up to £2,000 for a pair of tickets. “I bought 4 tickets but I have now realised that I cannot go to the concert, and so I am selling them”, was the genuine description by one seller who was asking for £1400 for the 4 tickets within 10 minutes which had a face value of £220 + fees. Far be it for me to accuse anyone of lying, (heavens forbid…..) but you do have to wonder how anyone can spend nearly £250 (a weeks wage for many) on 4 tickets without realising that there is no way that they can go to the concert.

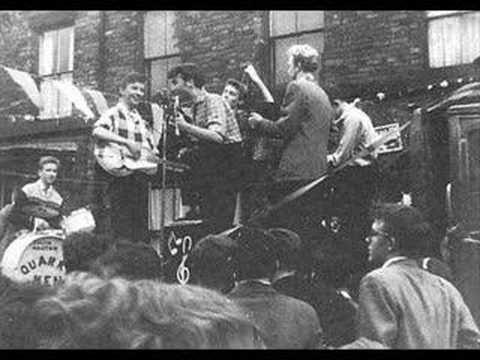

It is easy for tickets touts to easily take advantage because most bands will release an album a year, with one tour per album. If you miss one concert in your home town you may have a long wait until the next one, by which time the band may have moved onto a new era in their career or even changed their line-up. Your opportunity to see the band at that moment in time will be lost forever. With the greatest of respect to bands such as Status Quo (who are actually, by all accounts, a pretty entertaining live band), if you miss their concert and go to see them next year instead you will largely be treated to the same show both times in both the songs that they play and the style of performance. Missing their gig will just delay the show you will see, but it will be roughly the same show. Other bands develop at such a rate that the change would be a lot more drastic. Imagine seeing a band like Radiohead in 1992, or 1995 and then in 1998, or 2001. You would likely have seen 4 massively different shows, in both the songs and the instruments they play as well as their performance. The same goes for bands like Blur in 1993, 1997 and 2003, The Beatles in 1963, 1965 or 1968, and Steve Wonder in 1965, 1970 and 1975. Who wouldn’t pay that bit extra to see Nirvana as a 4 piece with Jason Everman on Guitar in 1989, or Pink Floyd as a 5 piece in 1968? I would.

To see such bands at different stages in their career is to capture, first hand, a band at a moment in their career that is a snapshot in time. The band may get better or worse in the future, but they will never be quite the same. You only have to listen to people who went to concerts such as The Stone Roses at Spike Island, Woodstock, The Monterey Music Festival, the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970 and Live Aid in 1985 to know how much it means to have been at such seismic events that are not only about music, but also about being a part of the generation that you grew up in, and witnessing the event that is the defining moment of that era. These concerts are not only about music, they help to give people an identity, a sense of belonging, and a reference point for their future years that they can use as a yard stick to measure future events against. In years to come these people may have years of working in a mundane job in an office which might fall well below what their 16 year old self would have expected, but what they see at this concert can be etched on their memory for years to come with a vivid idealism.

This explains the boom for re-union concerts – it gives people a chance to relive their youth or to replicate an event that they once missed. Much more important than buying their new album is getting to see a band live that reminds them of a time and a place that can never be revisited, but which for the right price can be temporarily recreated. The most lucrative tours ever include The Rolling Stones, “A Bigger Bang” tour, U2 “360 Tour”, The Police’s “The Police Reunion Tour”, as well as tours by acts such as The Eagles, Metallica, Cher, Roger Waters, AC/DC, Madonna and Bon Jovi. All of which are acts that hit their creative peak many years ago, with little risk of them ever reaching the same heights again. Instead of trying to eclipse the massive success that they had they are happy to literally play to the converted, and the fact that these concerts gross so much higher than some of the current biggest bands in the world shows how the lure of re-living the past is a much more powerful promotional tool than riding high on the crest of an commercial and creative wave. It is this emotional connection, for which there is no substitute for, that ticket touts use as leverage.

It is doubtful that there will be any steps from the UK government to fully eradicate stop this practice. In 2011 Labour MP Sharon Hodgson proposed that legislation should be introduced to cap the resell prices at face value +a maximum increase of 10%, but this was rejected by the Conservative Department of Culture, Media and Sport. It would seem the government actually wants legislation in place to allow the industry to thrive, which is in contrast to their philosophy of the sports industry. In the UK, the resale of football tickets is illegal under section 166 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 unless the resale is authorized by the organiser of the match, but music, comedy and theatre shows are all specifically exempt from this law.

Such an arrangement could easily be arranged for the music industry, both by the government and by the actual promoters themselves. After all, it is nigh on impossible to sell on tickets for the Glastonbury Festival on the black-market due to their insistence that the tickets are issued with the name of the purchaser, with people who attend the concert having to bring photo ID with them to identify themselves. That has virtually eradicated all levels of ticket touting and could easily be replicated across the industry. It would be naive to think that there is not the technology in place to eradicate the re-sale market, so one would have to assume therefore that the lack of any action taken is a route that the industry has decided to consciously take, as opposed to a decision that has been come to through the lack of an alternative or by being enforced upon them. As such, from this point of view it looks like music fans will simply have to accept ticket touting as a necessary evil in the industry, unless there is a drastic attitude change.

However, this is looking at the problem from the wrong angle. Concert goers should not be relying on the government or the music industry to help them out by reducing the cost of concert tickets. Instead it is both in the interests of the people who put on concerts (whether it be the bands, the venues or the promoters) and the people who go to these concerts that tickets are sold directly to the eventual gig goer since any money that goes to a middle man is less money that the end buyer can spend on more tickets, drinks and band merchandise when they get to the concerts, and that is to the detriment of both bands and fans alike. Being in a band is great fun but it is also a job for many, and when ticket touts look to profiteer from the strong demand that bands have worked incredibly hard to build up, with all of the costs that they have had from doing so, it takes money away from bands and their audience. Thus, both the buyer and the seller should be united in their desire to remove touts from the equation as it will mean more money for the sellers, and more concerts for the buyers.

A possible solution.

A possible solution for how to eradicate or vastly reduce the scale of ticket touting is surprisingly simple. At present ticket touts know that more people want to go to see a concert than can see it, and they use the level of demand for tickets being greater than the supply as their bargaining tool. It’s basic economics: if demand is greater than supply, prices go up. If you want to keep the price low you either try to decrease demand (which isn't possible) or you increase supply, and that is what the music industry needs to focus on - increasing the supply of tickets, and keep on doing this until the supply of the tickets reaches a level where the market balances itself, and supply outstrips the demand. That would eliminate the problem of fans having a limited choice as to where to buy their tickets from.

Here is how it would work in practice. A promoter would pick one huge band, for example The Rolling Stones, Coldplay, U2, or even match up several bands, such as a triple header of Foo Fighters, Muse and Arctic Monkeys, or for the Pop audience Katy Perry, Taylor Swift and One Direction. Whoever they choose, they need to pick a line up that will have a massive demand, and then announce a supply of tickets that is sure to sell out. They announce a concert on, for example, Saturday March 5th. The gig is located outdoors, and there are 50,000 tickets available. The tickets go on sale, and they sell out within 10 minutes, as expected. All they have to do now is add another date, for example, on Sunday 6th March. The stage is still set up from the day before, the bands are already in town, and the relevant permissions have already been granted, and, importantly, the bands know that they may need to play extra gigs, and have agreed to it. Adding a second date would bring with it an increase of effort, some extra costs, but a huge rise of revenue. Now there is a second concert, anyone who wanted tickets to the first show that was not quick enough can now get tickets to the next day instead of going to a tout. If that concert also sells out, then you add a 3rd concert to the show, for example, on Friday 4th March. If that sells out, then just add another one, on Thursday 3rd March and you just keep adding more and more shows, one at a time, as long as they keep on selling out. Every single time a concert sells out, you just keep adding another one, and you never stop. While the tickets are selling, you never stop. Even if it reaches 100 concerts, keep adding more and more. If you are able to charge a good ticket price, say £45 a ticket, that would bring in a revenue of £2,250,000 per concert, and every time you announce a new concert, you keep earning more and more revenue.

If you keep on adding concerts and they keep on selling out: - The bands are making big profits each gig from those ticket sales. - Lots of people are able to get tickets direct from the sellers. So long as they keep on buying them, they'll always be more available. - Staff/tech crew working the venue are getting extra shifts for each concert, and the venues are making a profit on the hire fee. - The profile of the band is being raised massively from all of the sold out stadium concerts and the extra press attention from the ticket sales. The only person who loses out is the ticket tout who is lumbered with tickets they cannot sell.

The market for who is buying these tickets can then be divided into 2 markets – people that want to go to the concert themselves, or people who are buying the tickets so that they can sell them onto other people for a profit. The people who buy the tickets for the music get what they want, the chance to see their favourite bands at a cheaper price from buying them directly from the band's promoter, and the people who bought the tickets to sell on are now stuck with tickets that are difficult to sell. Why would people want to buy from a tout at an inflated rate or even at the same rate when they can buy from the officially ticket retailer without the risk of them being fake. Suddenly the consumer has a choice of where to get their tickets from, and they don't need to pay over the odds from the panic of potentially missing the show altogether, which is a huge factor in them paying the inflated price to the tout. You have now taken away the only selling power that touts have, playing them at their own game.

If the band reached a stage where they could not keep adding dates, then they could look into expanding the capacity of the current concerts that they already have. So if they have 20 concerts selling out to 50,000 people each, they can ask for permission to expand each concert to a capacity of 51,000. That would free up another 20,000 tickets. If those sell out, expand each of the concerts again to 52,000 each, freeing up another 20,000 tickets. Keep on going until sales are under capacity/not selling out. On one hand it would be less exciting to be playing the same venue so much, on the other hand bands could feasibly be playing 40 concerts at the same venue in a row – it would be a bit like a tour but without the traveling (which can be tiresome) the soundchecks (boring), and the promotional activities (who needs to promote these shows when they keep selling out?). They can turn up to the venue every night, play the concert and then go to their hotel with a huge pay day and less expenses to match. Nice work if you can get it. They're getting all of the benefits of touring without the downsides.

As well as providing people with an opportunity to buy tickets at face value, it will have an important effect on the whole culture of music ticket touting. If you stick to certain concerts, the ticket touting industry is relatively risk free. Certain concerts are always going to have a much greater demand than the supply, and they will always be targeted by touts. The bigger the band, the less risk for the touts as they know that the increased demand swings the balance of power in their hands. However, if people within the music industry decided that a few times a year such a scheme would happen, it would suddenly bring in a massive element of risk to the touts. If any band released any tickets for some large concert, it will always be in the back of the mind for that tout, “What if this is the concert where they keep on releasing more tickets?” The tout could be left out of pocket. When the risk is there, they will always have to be much more cautious. The more cautious there are, the less tickets they will buy, and the more real music fans will be able to buy these tickets directly. Also, ticket touts need some initial seed money to buy the tickets in the first place. If you put a huge limit on the amount of tickets that people could buy, for example allowing them to buy 100 tickets each, you could have a situation where a tout buys 100 ticket for £45 each thinking that they can sell the for £100 each and make a huge profit, but when more concerts are announced, now they are stuck with £4,500 worth of tickets that will either be impossible to sell, or that they will need to sell at well under market value to claw back some of their money. This hurts their chances of any more touting activity in the future, and takes away the money that funds future touting.

If the touts had to keep on dropping their prices to claw back some of the money that they invested, there would now be a mass of cheap tickets coming onto the market which could open up a secondary market of people who would not otherwise plan to go to that concert, including people who are not massive fans of the act who are attracted by the cheaper price, as well as people who are big fans but otherwise would not have had the money to buy these tickets. More people get to see a band they would otherwise not have seen, and so the bands get to widen their audience. The only down side to such a scheme is that if the touts were unable to sell their tickets, many of the gigs may be emptier as a result. Under such a situation, it would be important to pick a venue that could potentially accommodate a large amount of people, but also one that could just as easily host a smaller amount of people if needs be without it affecting the success of the concert. If you picked a football stadium it would be noticeably half empty, but if it was a park gig, for example, this would not be as noticeable as venues such as Hyde Park are able to hold 65,000 people at it’s concerts, yet festivals such as Field Day are also able to hold 6,000 people and still have a good atmosphere at them.

Have 2 stages set up, and if there are many people at the concerts, use the bigger stage. If there are less, use the smaller stage. It is unlikely that it would ever affect the quality of the gig to have “only” 20,000 people there, as opposed to 50,000. If anything, it could make for a much better concert for those who attend since more people could get closer to the stage, the toilets, catering and bar lines would only be half the size, the security would have a much easier task with less people to control, and the trains would be half as crowded on the way home. All those tickets sold to the tout have generated the revenue to provide excellent faculties for this concert. The only scenario where a concert is ruined is if you have a stage set up for 70,000 people where only 10,000 are watching it – but if this were to happen, just think of how much of a loss the touts would have made? 60,000 tickets would have been wasted. Crippling losses for the touts.

The key to any investment is confidence. When 9/11 happened instantly the share price for airlines started to plummet as the unpredictability of the market scared investors off. The same would happen even if there was one attempt to flood the market with cheap concert tickets. One scheme could decimate the ticket touting industry

Comments